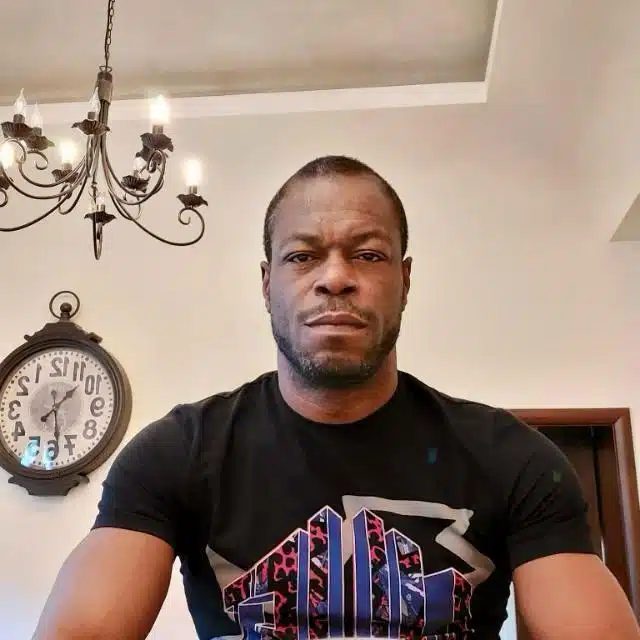

For over a decade, northern Nigeria has been a landscape scarred by fire, fear, and death. Behind the staggering statistics of killings and displacements caused by Boko Haram’s insurgency, lie individual stories, stories that cut deep into the heart of what it means to survive. One such story is that of Adegboro Micheal Oluwafemi, a quiet young man whose only “crime” was that his family chose Christianity over Islam more than three decades ago.

Now living in Romania, Oluwafemi rarely talks about what happened to him in 2013. When he does, it comes in fragments, like pieces of a broken mirror he’s trying to hold together.

“It started like any other day,” he said. “I was at the bus stop waiting to travel, then suddenly, motorcycles surrounded us, 20, maybe 30 of them. Then a bus pulled up, and before I could run, I was taken.”

Oluwafemi was among 19 people abducted in what seemed like a coordinated sweep by Boko Haram, the extremist sect whose name means “Western education is forbidden.” Known for their brutal tactics suicide bombings, school abductions, and executions the group has carved terror deep into the lives of millions. But Oluwafemi’s abduction was personal. It wasn’t just about power or territory. It was revenge.

“They knew my name,” he recalled. “They were shouting Danladi Oluwafemi the Muslim name I had before my family converted in 1980. They called us traitors. To them, leaving Islam is worse than anything else.”

The abductors transported the group by bus for an hour, watching them closely. At intervals, Oluwafemi’s old name was called, perhaps to bait him out. He remained silent, frozen in fear. Then came a moment he can never forget.

“One of the other captives, maybe thinking he could protect me or maybe confused answered to the name. They shot him instantly. The woman beside him too.”

Oluwafemi fell silent during the interview, his eyes heavy with memory. “I could feel my heartbeat in my throat. That could have been me.”

From there, the captives were marched barefoot through the forest for nine hours a test of physical and mental endurance. They were offered no water, no food, just the unrelenting bush path and the occasional threat from armed guards.

“They didn’t just want to imprison us,” Oluwafemi said. “They wanted to break us.”

At the end of that trek lay a jungle encampment a place where hostages were typically held for indoctrination or forced labor. But Oluwafemi’s survival instincts refused to quiet down.

“One night, one of the guards stepped away. It was just a few seconds, but it was enough. I ran. I didn’t stop. I don’t know how I made it. I just kept going until I found a village.”

Oluwafemi’s escape was a miracle but a lonely one. “The others… they didn’t make it. They all died. Maybe shot, maybe from hunger. I don’t know. But I was the only one who came out.”

The trauma of what he witnessed doesn’t fade with time. It lingers in his voice, in the way he avoids cameras, and in his deep mistrust of loud noises. In Romania, far from the chaos of Nigeria’s northeast, Oluwafemi tries to rebuild. But every day, he carries the burden of memory of those who didn’t escape, and of a country still bleeding from wounds no one wants to name.

Boko Haram’s campaign of violence has displaced over two million people, with entire villages wiped out and generations traumatized. Their attacks are not only religious; they are deeply political, often exploiting weak governance, poverty, and broken education systems.

But as Oluwafemi’s story shows, beyond the geopolitics and headlines are people, people caught in the crossfire of ideology and extremism.

“I wasn’t trying to be a hero,” he said. “I just wanted to live. That’s all.”

In Oluwafemi’s survival lies a painful but necessary reminder: the fight against terrorism is not just about guns or borders it’s about healing lives that have been shattered in silence. And unless those stories are told, and truly heard, the path to peace will remain a distant dream.