Who owns the media, and for what purpose? That question has once again taken centre stage in Nigeria’s democracy, as concerns grow about how business interests, profit pressures, and ownership structures shape the news citizens consume.

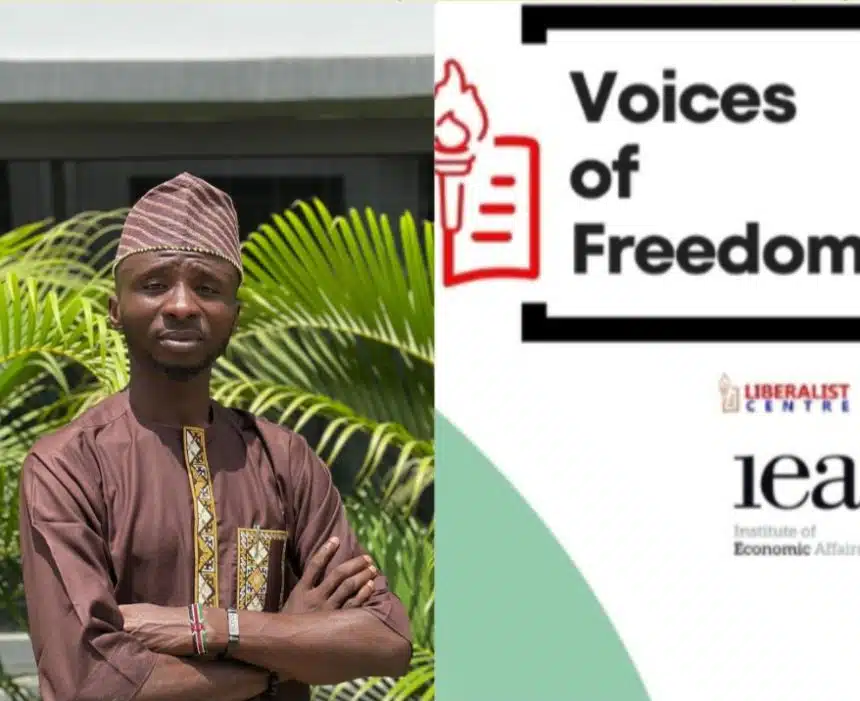

Speaking on Voices of Freedom on Adamimogo 105.1FM, Taoheed Adegbite, Online Editor at the Nigerian Tribune, unpacked the sustainability challenges facing media organisations and why ownership matters in safeguarding press freedom. The programme is part of the Liberalist Centre’s Journalism for Liberty Fellowship, with support from the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) and Atlas Network.

Media as Public Service or Profit Machine?

Adegbite argued that media platforms should ideally be seen as public-interest institutions rather than purely profit-making ventures.

“Running a media organisation is not like running a fast-food business. It’s rarely about immediate profit. Many people who establish media houses do so to give back to society, to leave a legacy of informing the public,” he explained.

However, when profit becomes the overriding motive, editorial independence suffers. “If all you’re interested in is balancing the books, then you risk sacrificing impactful journalism for commercial survival,” Adegbite warned.

The discussion turned to the ways advertisers, owners, and political allies influence coverage. Adegbite described this as a long-standing problem of “friends of the house.”

“Everybody knows that if you are a close ally of a media organisation, your story may be treated differently,” he said. “But ethical journalism demands balance, even when reporting on advertisers or powerful stakeholders, we must still include other perspectives.”

He noted that while commercial interests are inevitable, responsible media houses strive to protect credibility by giving all sides a voice.

“Integrity is a survival strategy. If you block opposing views today to please a big advertiser, tomorrow you may lose both your credibility and your advertiser.”

Is Democracy at Stake?

Adegbite stressed that media ownership has direct implications for democracy. “When the stories citizens see or don’t see are shaped by hidden interests, democracy suffers. The media must remain a platform for diverse voices, not just the loudest or richest ones.”

This resonates with growing debates in Nigeria about media capture, where political or business elites dominate information flow.

What Can Citizens Do?

Asked how audiences can navigate today’s crowded information ecosystem, Adegbite advised Nigerians to stick with platforms they trust.

“With social media, everyone is a publisher. But credibility is still earned by legacy institutions and professional outlets. Before believing or sharing, ask: if this report turns out false, does the platform risk its integrity? That’s the kind of standard audiences should look for.”

Many outlets struggle financially, making them vulnerable to capture by advertisers or political benefactors. Yet, Adegbite’s message was clear: journalism that safeguards democracy must prioritize credibility and service to the public above short-term profit.

“Media ownership matters because it shapes narratives and narratives shape societies. If we want a freer, stronger democracy, we must also fight for independent, sustainable journalism,” he concluded.